In this post, we will discuss one of the two recognized types of parallelism (task and data).

- Task parallelism (also known as function parallelism or control parallelism) as the name suggests distributes work across multiple processors. Task parallelism distributes processes across the processors or nodes. This is different from the second type of parallelism, data parallelism.

- In data parallelism, it is the information that is distributed across processors. An example of data parallelism is taking a summation of values in a data array. In data parallelism, groups of numbers are sent to each core to do the addition. Those values are then added on a smaller group of cores until a single number is computed.

Task parallelism sends a unit of work to a processor. In our summation example, a single processor is responsible for calculating the sum of a single data array while maybe another processor does that task with a completely separate array.

If you are interested in data parallelism, this post is not for you. A lot of work has been done on the topic and enabled within the IPython environment. I would suggest checking out Using MPI with IPython.

OK, why do I care?¶

The current belief is that human time costs more than computer time. If you can get more done using most of the resources available for your machine, then the work gets done faster and you the human can interpret the result. All right, so if you are saying to yourself that this sounds awesome but I'm not a computer scientist, you don't need to be. The great contributors to Python have done that work for you.

What is the difference between multithreading and multiprocessing?¶

The multithreading paradigm allows multiple requests to be managed by the same program without running multiple copies. Multithreading is typically used on systems with a single CPU. In multiprocessing, multiple processes or jobs can be run and managed by the CPU or a single program. This is how you are able to have a browser running in addition to a word processor. We are going to deal with the latter. If you are interested in multithreading, there are a handful of tutorials available.

Ok, you've talked a lot about what we aren't covering!!! Let's get started!¶

Yes, let's get back to multiprocessing! Python's multiprocessing library has a number of powerful process spawning features which completely side-step issues associated with multithreading. As a result, the multiprocessing package within the Python standard library can be used on virtually any operating system. Setting up multiprocessing is actually extremely easy!

To use the multiprocessing package, we must define a 'unit of work.' This 'unit of work' contains everything we want done in a single task. Let's jump into an example.

IPython has some issues spawning subprocesses. To avoid these issues, we will save code to a file then run that file within the notebook.

%%file multiproc.py

import multiprocessing # the module we will be using for multiprocessing

def work(number):

"""

Multiprocessing work

Parameters

----------

number : integer

unit of work number

"""

print "Unit of work number %d" % number # simply print the worker's number

if __name__ == "__main__": # Allows for the safe importing of the main module

print("There are %d CPUs on this machine" % multiprocessing.cpu_count())

number_processes = 2

pool = multiprocessing.Pool(number_processes)

total_tasks = 16

tasks = range(total_tasks)

results = pool.map_async(work, tasks)

pool.close()

pool.join()

Use %%bash for Unix machines and %%cmd for Windows machines

%%bash

python multiproc.py

Discussion line by line¶

Let's skip down to the the line

if __name__ == "__main__":

For those of you not familiar with this line, it tells the Python interpreter to run this section of code when the script is not imported into another piece of code. You can think about it this way

if __name__ == "__main__":

print('The program executed by itself')

else:

print('The program has been imported from another module')

The Python documentation says that this is required when using the multiprocessing module in order to allow for "safe" importing of the main module.

multiprocessing.cpu_count()

The line above should be self-explanatory. However, it is important we still understand it. cpu_count() essentially tells us the theoretical maximum number of processes we can run at any given moment. If cpu_count() returns 10, in practice, you will never have 10 workers going at one time. Python turns out to be a polite program. If it sees other processes are running on the machine, it may only use 8 or 9 out of 10. This is important for the next two lines of code.

max_number_processes = 2

pool = multiprocessing.Pool(max_number_processes)

In the first line, I set a maximum number of worker processes that multiprocessing should run at any given moment. Each worker is assigned its own process identification number (pid). You will notice that I stayed on the conservative side by picking 2. However, Python will allow you to set the value to cpu_count() or even higher. Since Python will only run processes on available cores, setting max_number_processes to 20 on a 10 core machine will still mean that Python may only use 8 worker processes.

total_tasks = 16

tasks = range(total_tasks)

results = pool.map_async(work, jobs)

OK, the next two lines are where the magic really begins to happen! In this case, we are using map_async. We will skip what this means for now but map_async assigns work to the worker processes. To define the 'work' done by the worker processes, we pass a func I've called work as the first argument in map_async and an iterable, which I defined as tasks, that is a list of integers using range(). tasks is any iterable Python object. It contains all the args you want to pass to work. I'll show a more complicated and more useful iterable later.

It is important to note two things about what we've done. The first is that the number of tasks, 16, is greater than the theoretical maximum number of processes we can run. This means when a worker is done with 'one unit of work,' it moves on to the next. The next note is that map_async does the work in random order and does not wait for a proceeding task to finish before starting a new task. This is the fastest approach, but it means that Unit of work number 6 may print before Unit of work number 2. In this case, we aren't worried about that.

The last two lines of code I discovered through painful trial and error.

pool.close()

pool.join()

OK, so close() means that we cannot submit new tasks to our pool of worker processes. Once all the tasks have been completed, the worker processes will exit. This is required before we can run what's probably the most important line in this example, join(). join() says that the code in __main__ must wait until all our tasks are complete before continuing! Why is this important? Well, if you plan to use the results returned by your worker processes, you must make the code pause. If you do not use join, the remainder of your script will run after map_async spawns, assigns the tasks, our worker processes. This means you may get errors and other parts of your code will throw a NameError or another ugly error.

OK, so in this example, we didn't do anything too interesting besides introduce the basic structure of a multiproccessing Python script. Please note that you can always import a func you plan to use for your 'unit of work.'

Measuring performance gains¶

Now that we know what multiprocessing is and how to write a Python script which uses the package, how do we know whether or not we've gained anything? In parallel computing, we can evaluate our performance with a few metrics. This is a great exercise in determining what the value of max_number_processes. On a quick sidenote, while Python maybe polite up to a certain extent, please make sure that if you are using a shared machine with multiple users, you do not completely take over the system.

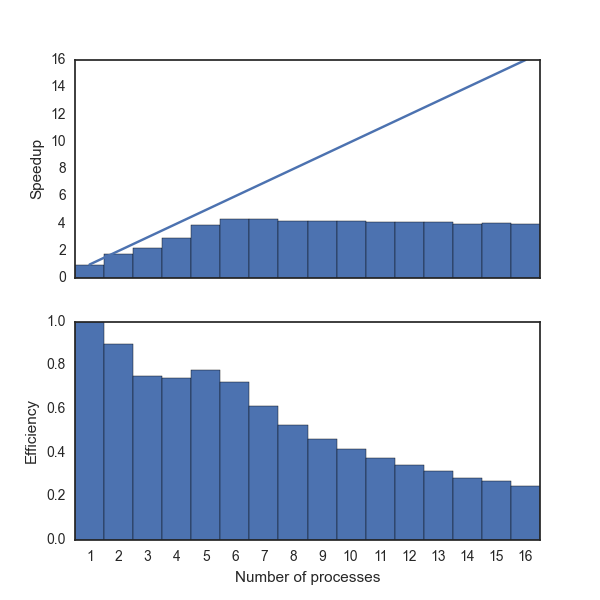

Speedup¶

Speedup is a metric used to assess the relative performance improvement gained by executing one task versus another. In parallel processing, we say the task is all the work we'd like to get done. In our case, we are comparing serial execution (a single process) of all the work versus a task parallelism version. Speedup is defined as $$ S \equiv \frac{T{\text{Old}}}{T{\text{New}}} $$ where $S$ is speedup, $T_{\text{Old}}$ is the time taken to execute the script without improvement (Serial), and $T_{\text{New}}$ is the time taken to execute the script with the improvement (Parallel).

Efficiency¶

Theoretically, speedup should be linear in that $S$ is equivalent to the number of processors. We would expect $$ S_p = p $$ where $p$ is the number of processors and $S_p$ is the speedup in parallel computing. In practice, we never see this type of speedup. So, we come up with a new metric that we'll call efficiency. We'll define efficiency as $$ E \equiv \frac{Sp}{p}=\frac{T{\text{Serial}}}{pT_{\text{p}}}. $$

In both cases, we are using the simplest forms for the definitions of speedup and efficiency. Parallel code is typically a blend of serial and parallel. Amdahl's law and Gustafson's law are likely more accurate but for our purposes, we'll look at the relative improvements.

Our test¶

Let's define a test in which we increase the number of worker processes from 1 to cpu_count * 2 + 1. We'll run each value for max_number_processes several times then average the time taken. From here, we will plot speedup and efficiency. Expect the results that I get to be vastly different than those on your system. Please note that this script can take time to run.

%%file performance.py

import multiprocessing # the module we will be using for multiprocessing

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import time

from itertools import repeat

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_style("white")

def work(task):

"""

Some amount of work that will take time

Parameters

----------

task : tuple

Contains number, loop, and number processors

"""

number, loop = task

b = 2. * number - 1.

for i in range(loop):

a, b = b * i, number * i + b

return a, b

def plot(multip_stats):

"""

plots times from multiprocessing

Parameters

----------

multip_stats : dictionary

dictionary containing time running

"""

serial_time = multip_stats[1].mean()

keys = multip_stats.keys()

keys.sort()

keys = np.array(keys)

speedup = []

efficiency = []

for number_processes in keys:

speedup.append(serial_time / multip_stats[number_processes].mean())

efficiency.append(speedup[-1] / number_processes)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(211)

plt.plot(keys, keys)

plt.bar(keys-0.5, speedup, width=1)

plt.ylabel('Speedup')

ax.set_xticks(range(1, keys[-1] + 1))

ax.set_xticklabels([])

plt.xlim(0.5, keys[-1] + .5)

ax = fig.add_subplot(212)

plt.bar(keys-0.5, efficiency, width=1)

plt.ylabel('Efficiency')

plt.xlabel('Number of processes')

ax.set_xticks(range(1, keys[-1] + 1))

ax.set_xticklabels(range(1, keys[-1] + 1))

plt.xlim(0.5, keys[-1] + .5)

plt.savefig("./parallel_speedup_efficiency.png")

if __name__ == "__main__":

cpu_count = multiprocessing.cpu_count()

print("There are %d CPUs on this machine" % cpu_count)

number_processes = range(1, cpu_count * 2 + 1)

loop = 1000

total_tasks = 1000

tasks = np.float_(range(1, total_tasks))

number_of_times_to_repeat = 20

multip_stats = {}

for number in number_processes:

multip_stats[number] = np.empty(number_of_times_to_repeat)

for i in range(number_of_times_to_repeat):

pool = multiprocessing.Pool(number)

start_time = time.time()

results = pool.map_async(work, zip(tasks, repeat(loop)))

pool.close()

pool.join()

end_time = time.time()

multip_stats[number][i] = end_time - start_time

plot(multip_stats)

%%bash

python performance.py

The figure below shows the speedup and efficiency improvements for the case above. It is always a good idea to conduct a similar test for your system and code with the goal of finding the optimal number of processes. From this example, we can see that our speedup maximizes around 9 processes. Why 9 when the machine has 8 CPUs? Since other processes can be running on the machine, we will never see an optimal speedup of $S_p=p$. Why we are we allows to have more than 8 processes when we only have 8 CPUs? As we mentioned earlier, we can have more workers than CPUs. However, the workers currently working is limited to the available CPUs. But, it is worth noting that while we maximized at 9, we never see our ideal/theoretical speedup. Efficiency paints a clearer picture of this metric.

The actual results will vary wildly based on the system and the other processes running on the system.

Why is the plot so noisy? The "noise" you see in each bar is related to the number_of_times_repeat. The higher the number, the more likely we will see the true distribution on the machine. The variation will be cause by other processes running on the system and operating system level jobs running concurrently.

Exploiting multiprocessing to get around a Python 2.x bug¶

I recently ran into an issues with Python 2.x. Luckily, it isn't a problem in Python 3.x so it is probably time to upgrade. However, I run code on a number of operational machines which will likely not upgrade to Python 3.x for another 5-10 years. What is the issue? I noticed that some of my scripts would hog a large amount of RAM in time. After a task within the script was completed and the next started, the RAM usage would double as if the RAM was never cleared. That's probably fine for small scripts but I crashed several systems which ran out of RAM. What was going on?!?! Whatever it was, it has to be stopped or I need to switch to another language (shudder).

It turns out that Python does its job and correctly garbage collects after each task is complete. OK, that information isn't helpful. However, I use a number of packages like NumPy, SciPy, and matplotlib which wrap compiled C code. Apparently, it is a known issue that the C libraries receives Python's garbage collection signal but doesn't use it. Python thinks it did its job but C failed to clear the RAM. It is my understanding that the Python developers will not fix this for Python 2.x.

OK, so what do we do! Here is the aha moment. The RAM is freed when the process ends (if you didn't crash the machine before that). What if we use multiprocessing? As I mentioned earlier, each worker process has its own process ID. When a worker finishes, it releases its RAM. However, each worker process could still take up more than its fair share of RAM. Never fear! A Python keyword argument is here! multiprocessing.Pool takes a keyword argument called maxtasksperchild. maxtasksperchild sets how many tasks a worker process is allowed to do. In order to skirt our issue, all we need to do is maxtasksperchild=1. OK, but wait, if we need to run 30 tasks and only set max_number_process to 2, don't we run out of workers? Luckily, no! multiprocessing only allows 2 workers to exist at any given time so Python keeps generating workers until the close() and join() are called.

In the example below, I also included some memory profiling information.

%%file py2bug.py

import multiprocessing

import resource

from itertools import repeat

import numpy as np

import sys

def work(task):

"""

Some amount of work that will take time

Parameters

----------

task : tuple

Contains number, loop, and number processors

"""

number, loop = task

b = 2. * number - 1.

empty_array = np.ones((loop, loop))

for i in range(loop):

a, b = b * i, number * i + b

print('\tWorker maximum memory usage: %.2f (mb)' % (current_mem_usage()))

return a, b, empty_array

def current_mem_usage():

return resource.getrusage(resource.RUSAGE_SELF).ru_maxrss / 1024.

if __name__ == "__main__":

cpu_count = multiprocessing.cpu_count()

print("There are %d CPUs on this machine" % cpu_count)

loop = 1000

total_tasks = 15

tasks = np.float_(range(1, total_tasks))

print("Same worker for all tasks:")

pool = multiprocessing.Pool(processes=1, maxtasksperchild=total_tasks)

results = pool.map_async(work, zip(tasks, repeat(loop)))

pool.close()

pool.join()

del pool

print('Global maximum memory usage: %.2f (mb)' % current_mem_usage())

print("Respawn worker for each task:")

pool = multiprocessing.Pool(processes=1, maxtasksperchild=1)

results = pool.map_async(work, zip(tasks, repeat(loop)))

pool.close()

pool.join()

del pool

print('Global maximum memory usage: %.2f (mb)' % current_mem_usage())

print("Use a Python loop:")

mem_usage = current_mem_usage()

for task in zip(tasks, repeat(loop)):

a, b, empty_array = work(task)

print('Global maximum memory usage: %.2f (mb)' % current_mem_usage())

%%bash

python py2bug.py

In this example, you can see that the serial case slowly grows in time. This isn't a very dramatic difference but we aren't doing much in our work function. You can imagine that in a bigger program how repetition could cause problems. Another thing to note is that just using 'multiprocessing' helps eliminate some of the issues with memory since the main program is isolated from the worker as a seperate process as the example shows. In both of the 'multiprocessing' instances, memory usage fluctuates. Respawning potentially uses more memory per task since the CPU must continually reallocate RAM. In reality, you must find the best method for your problem.

Concluding remarks¶

In this post, we have explored the task parallelism option available in the standard library of Python. We have shown how using task parallelism speeds up code in human time even if it isn't the most efficient usage of the cores. We also explored how task parallelism can be used to avoid the Python 2.x memory bug.

This post was written using an IPython notebook. You can download this notebook, or see a static view here.

*Please note that Multiprocessing: Task parallelism for the masses by Chris Slocum is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.*